This Epiphany, we have reintroduced the appointed psalm into our Sunday lectionary readings. A wonderful tradition of the Anglican heritage is that of Anglican Chant, which is the practice of chanting the psalms. In contrast to Gregorian Chant (which is what most people think of when they think of “chant”), Anglican Chant feels a little more like hymn-singing, with its more familiar, balanced phrase lengths and harmonic movement.

At Nativity, we don’t have a long-standing tradition of Anglican Chant. However, chanting is not as difficult as many think. Last week — the First Sunday after the Epiphany — we recited the psalm antiphonally. This Sunday, we will chant the psalm using what’s known as Simplified Anglican Chant. Simplified Chant is a good introduction to the tradition of Anglican Chant, for a couple reasons:

- the chants are much shorter (usually half the length of full Anglican Chant)

- the chants are in unison, with everyone singing the same melody (unlike Anglican Chant, which is in four parts)

Our plan, as we reintroduce this practice into our liturgy, is to alternate reading and singing the psalm weekly.

Here are a few pointers (pun intended) to ease the transition into chanting.

What do the symbols mean?

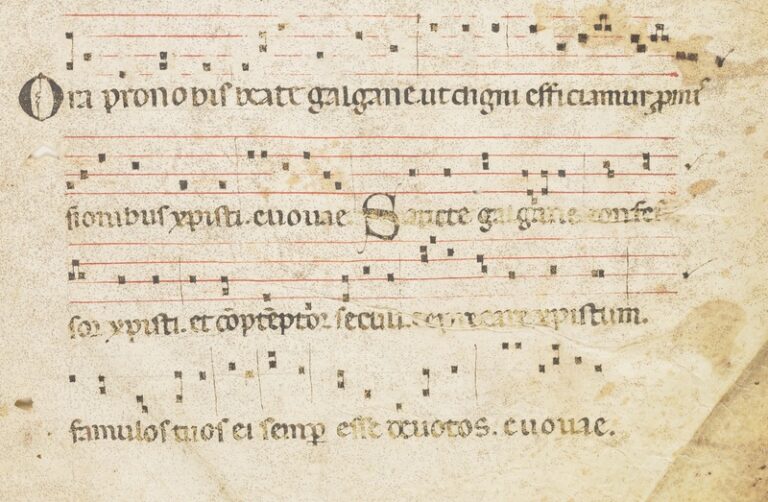

The psalms are “pointed”, which means that certain symbols are used to tell you when to change note. There are two main symbols in the text that we need to know to get started: the asterisk (*), and the slash (/).

The slash tells you when to change note. Most of the text is sung on what’s called the “chanting” note. These notes are white, or not colored in. The word(s) after the slash — usually only one or two syllables — are sung on the “moving” note. This is a black note, or a note that is colored in.

The asterisk indicates the half-way point of the verse. In the simplified chants, there is a “double bar line” in the music. This is important, because on odd-numbered verse psalms, we have to end with the second half of the tune. (The complete tune takes two verses of text to sing, so this ensures that we end the chanting with the end of the tune.)

Putting it all together, here is how the first two verses of Sunday’s psalm are realized:

It’s all about the text

Even though many Gregorian and Anglican chants have beautiful melodies, the text is really where the focus is. It’s quite possible to chant an entire passage on one note, and that is actually frequently done in some circles. (If you came to Evensong with the Raleigh Convocation Choir in December, you would have heard or participated in reciting the Apostles’ Creed in unison on one note.)

With the text being the central focus, it’s important to remember the natural rhythms of speech. It’s very easy to fall into the trap of chanting the same way you sing a hymn. But the text should dictate the rhythm and tempo (speed) of the chant — much as if you were speaking it.

— Bradley Burgess

Nicely put! And helpful.